Stories:

The Fifteenth Amendment

During the Reconstruction of the United States after the Civil War, the Republican Party tried to enfranchise former slaves. Its efforts on this front proceeded in two steps. First, Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, provided that “when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State” (emphasis added). While this did not directly enfranchise Black men, it punished Southern states for disfranchising them by depriving Southern states of representation in Congress exactly to the extent that they did so. In this way, the Fourteenth Amendment provided an incentive for Southern states to remove racial barriers to the ballot box. (In theory, it did the same for Northern states, but as Northern states had much smaller Black populations, the effect of the Fourteenth Amendment on their congressional representation was slight.)

As Reconstruction progressed, the Republican Party became more radical, and the Fourteenth Amendment proved an insufficient means of enfranchisement. In 1869, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment, which was ratified a year later. It did what had been politically unthinkable a mere decade before: It guaranteed the right to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

After Reconstruction ended in 1877, when a moderating Republican Party agreed to remove federal troops from the South in exchange for the Presidency, Southern White supremacists embarked on an effort to undo the gains Blacks had made, especially regarding suffrage. These efforts, which really took off in the 1890s, when Southern states ratified a slew of new state constitutions, famously included the use of spurious literacy tests and poll taxes, which otherwise enfranchised citizens had to pass or pay before being allowed to vote. Less famously, they included attempts by Southern members of Congress to repeal the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments not only practically but textually.

Sources of Anti-Enfranchisement Constitutional

Amendment Proposals, 1900–1915

Between 1900 and 1915, Southerners in the House and Senate (and one Pennsylvanian, scolding his “old-fashioned” colleagues who “refus[ed] to recognize the doctrine that ‘the Constitution should not be permitted to stand between friends’”) introduced thirty proposals to repeal either the Fifteenth Amendment or Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment, or both. These proposals did not represent a concerted effort by Southern White power generally to modify the Constitution. All but one were proposed by members of the House of Representatives, a large body whose members have small constituencies and thus, by design, tend to be a more diverse and idiosyncratic lot than their counterparts in the Senate. For each of Alabama, Mississippi, and North Carolina, the multiple proposals came from just one representative. (Seven of the total eleven proposals to repeal Section Two of the Fourteenth were from future governor Thomas Hardwick of Georgia.) Every one of these proposals died in committee, and whether they were intended actually to effect a change to the Constitution or simply to express support for the principle of racial disfranchisement is unclear, though the latter seems more likely.

Still, they embody a dissatisfaction among Southern White supremacists and their Northern allies with the practical victory over the Constitution’s restrictions on disfranchisement that they had already achieved, and the identical wording of the Fifteenth Amendment repeal proposals indicates that, even if the vocally dissatisfied did not speak for a major political party or a mass movement, they identified themselves with one another. The proposals also serve as a barometer for where racial revanchism was most intense at the turn of the twentieth century, both geographically–even with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan across the West and Midwest, the proposals came overwhelmingly from the South–and politically–though the Southern proposers were all Democrats, the Pennsylvanian was a Republican, a reflection of the cachét White supremacy had garnered in the Republican Party by the 1910s.

Wording of Fourteenth Amendment Repeal Proposals, 1903–1913

Wording of Fifteenth Amendment Repeal Proposals, 1900–1915

This burst of amendment proposals targeting the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments was an anomaly in the sweep of American history. Before and after 1900–1915, the only attempt to repeal the Fifteenth Amendment was an 1877 proposal, of which no text survives, to “[r]estric[t]” the amendment’s ‘application.” Attempts to repeal the Fourteenth Amendment outside the time span were only slightly less sparse: In 1937, 1948, 1950, and 1973, members of Congress attempted to repeal the amendment wholesale. All of these proposals died in committee. Yet such measures began to resurface in the 1990s, in a series of proposals aimed at repealing the birthright citizenship provision of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Targets of Anti-Enfranchisement Amendment Proposals, 1900–1915

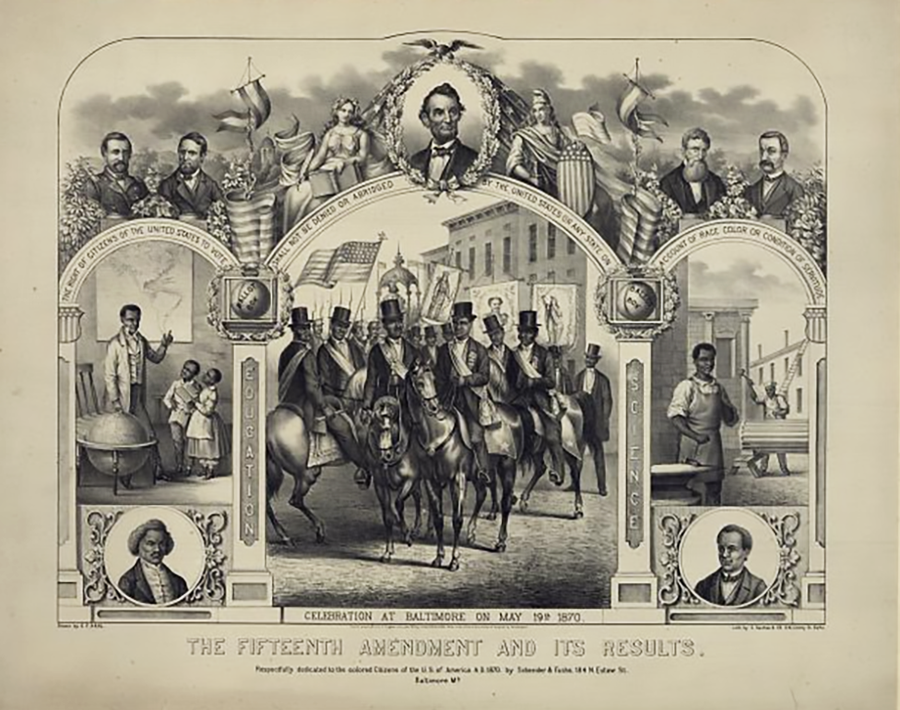

The Fifteenth Amendment and Its Results, 1870

This 1870 poster commemorates the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

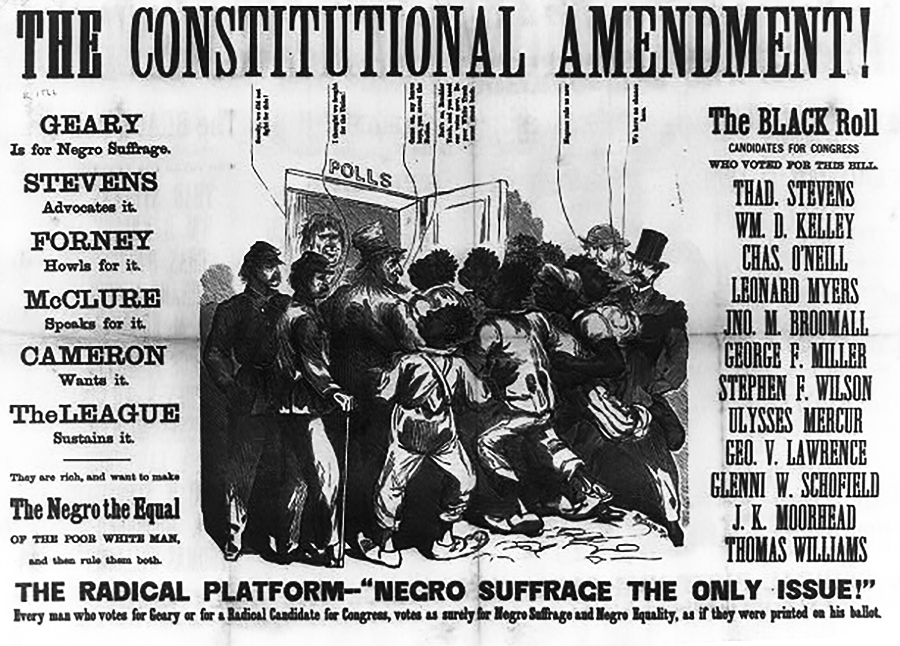

A Constitutional Amendment

Political poster, 1866, Library of Congress Rare Books and Special Collections Division. Opposition to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments was exhibited in a series of racist posters and political pamphlets published in the 1860s and 1870s.